Beggs – Exercise: Bottle, Jug and Lemon

The wattle and daub construction at Montsalvat provides yet another background to a still life.

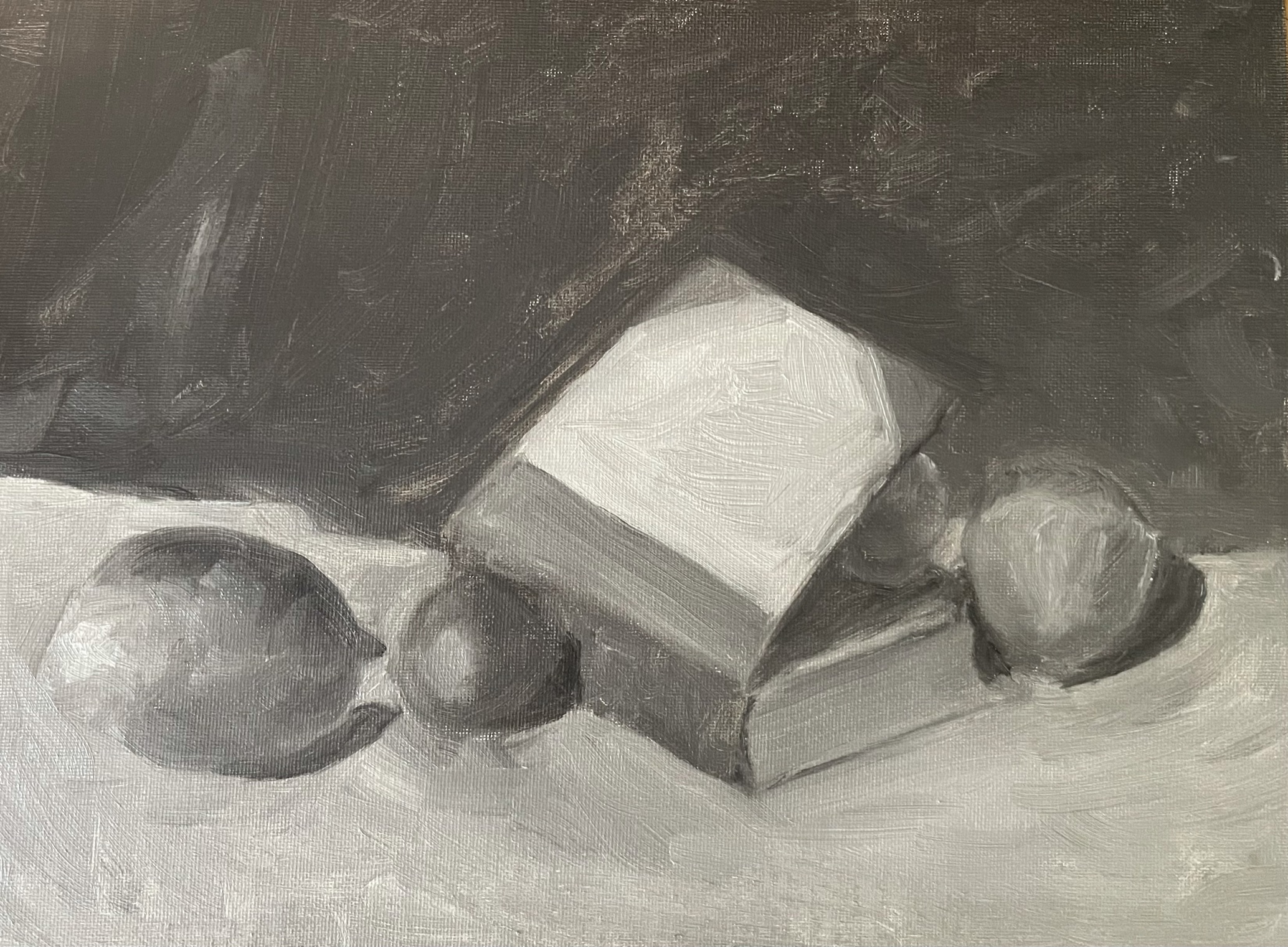

Each painting starts as a white canvas, to which is added little paint dots. The dots are measurements taken by eye and marked by a thumb on a paintbrush extended at arm’s length – a very arty-looking approach when viewed as a bystander (so of course, being me, I fell in love with this approach instantly). By standing at the same spot, I can measure a chosen starting object’s apparent height or width and then use it to place more dots for the extremities of other objects. For example, I started with the lemon, just by eye. Then established that the bottle is four ‘lemon heights’ high, and the jug is one and a half ‘lemon heights’ wide; the bottle’s base starts half way up the lemon, and so on.

From here (no drawing allowed) a few more reference dots are made of apparent heights and widths, and then you thinly paint in the object. Or you could start with the background instead (making the object appear as a negative space as the background surrounds it). No attempt is made at this stage to create depth or any other detail *within* an object, just getting the edges in the right places. By ‘objects’ I also include the major shadow shapes, whether within the object or cast by the object. But not too much within yet. The no-drawing approach keeps you free to change your marks, even to wipe out something. This was very hard at first, but once you get past that it definitely stops you being stuck with a wrong position, you’re just happy to wipe it out. (What looks like a pencil line near the right of the neck of the bottle is in fact the mark of a stray hair on my brush as I was creating the neck.)

The whole idea is not to become wedded to your first marks (which is why drawing is discouraged), but rather creep up on the exact locations of edges, their angles and their relationships to other objects. Deciding in which order to do this seems to come fairly organically, as you notice that the bottle is too thin, too wide, too short etc in relation to other objects. Using an extended paintbrush to establish an angle and then bringing it at the same angle across to your canvas can also help, uncovering subtle variations that will be amplified later if left unchecked.

I use multiple paintbrushes, starting fairly large. I also tend to keep a brush each just for darks, blues, reds and yellows. I usually only wipe on a bit of cloth or paper towel between colours, not being overly afraid of stray colour hues leaving subtle connecting thoughts between objects. The only colour I avoid until needed is white – of course I need it to get some of the colours I want, but I treat it like poison on my brush once used – needing a good clean out less it pollute my lovely darks.

The purpose of all of this is to represent reality. These exercises are not the time for ‘artistic licence’, we are here to learn how to represent what we see.

‘Seeing’, really seeing, is much harder that it might seem. Forms, colours and edges are not to be informed by what we think we know (which are mental shortcuts that are rarely correct) but what we actually see. For example, the wall is white. Actually, it’s not, it’s a range of colours, and almost none of them white. Hold a piece of white paper, or white window on your computer, against the wall and see how dark it really is. But if pressed by looking at it, or worse, trying to recall it, we would employ our mental shortcuts and not see the colour that is actually there. In this way our painting would move away from creating a realistic representation of reality, and move towards stuck-on looking objects in a child’s picture book.

Finally, after all of this comes the fun part (at least to me): establishing texture, three dimensions within objects, getting the darks right, and finally putting in the highlights.

There’s more to painting than meets the eye. Or, putting it a better way: the trick is to paint what actually meets your eye. Yep. Just do that and you’ll be fine. I must try that one day.

More from Geoff Beggs

Leave A Comment