Gallipoli

25 April 2015

What we learn at school becomes accepted wisdom. Simpson and his donkey. Our lads, doing our bit. For king and country. For victory. To rid the world of evil.

I walked over the beach at Gallipoli last May. Went to the top and saw the trenches. Lone Pine. The Nek. The Dardenelles. All the places whose names were familiar since I was a child. The simple gravestones, row after row. The lone pine tree – was this the one? There was no crowd, just me alone in the lowering cloud with the markers of loss in the green grass.

It probably wasn’t even the right beach; the beaches on either side afforded a much better way in. Militarily, it was pointless in any case. Like World War One itself.

Our attack, thousands of miles from home, made modern Turkey. Out of a number of possible but seemingly equal candidates, Mustafa Atatürk rose to prominence because of his victory at Gallipoli. Eventually he would create and lead modern Turkey. He told his men they were not there to do a job and go home. He told them they were there to die, defending their own country against attackers from a land far away, whose reason to attack them wasn’t really clear. It was our role to be the attackers, at the behest of Empire.

Our national myth about Gallipoli acknowledges that we failed; but doesn’t dwell on how pointless it was.

Our nation wasn’t born in bloodshed. The declaration of the nation of Australia in 1901 was not the result of a revolution or a battle. It was a political understanding between the various States. Of course, like many, I am conveniently forgetting the bloodshed over the previous 120 years of the indigenous inhabitants of the great south land.

Gallipoli was early in our declared nation’s history; our first large numbers of casualties in battle. Enough blood makes soil sacred, it seems. How else can you make sense of young men gone, screams, bullets, bayonets, blood, mud, pain and loss.

The memorials at Gallipoli are the graves, the statues and the words. The graves are sobering. The statues are not focused on victory, but on humanity. This one is of a Turkish soldier carrying a wounded ANZAC back to his lines. I’m not sure if I’ve seen anything like this elsewhere.

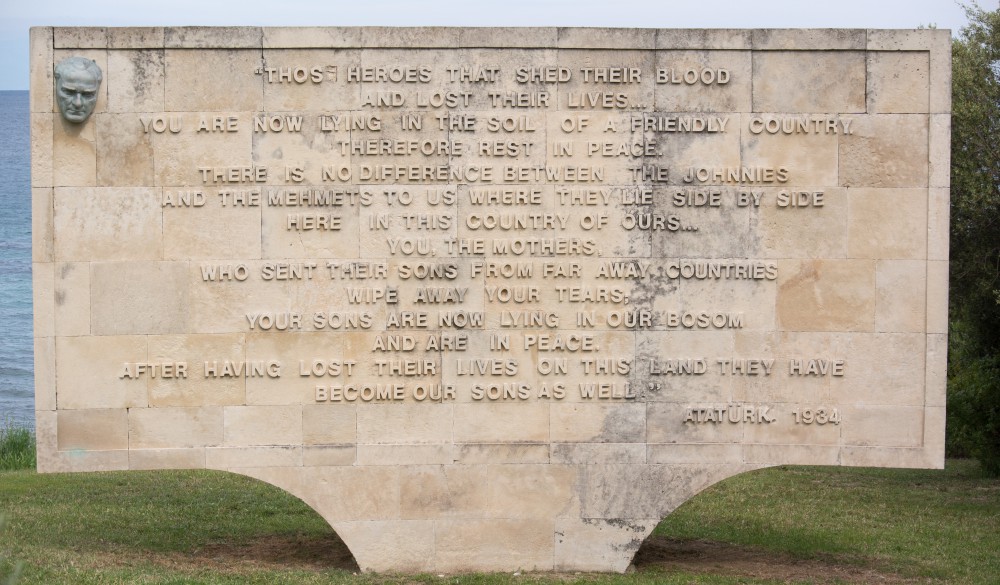

The words with the most prominence on the peninsula are those attributed to Atatürk (although there is some controversy about whether he penned them). And remember as you read these words, that the Turkish losses were many times ours: between 70,000 to 100,000 men who heeded Ataturk’s instruction that they were there to die. These words came later, but only about 20 years later, when the memory of loss would have been still fresh. They are carved in stone, underlining their permanence. They are written in Turkish on one side, and English on the other, for us. Whoever said them, they are generous and reflect well on a generous people.

THOSE HEROES THAT SHED THEIR BLOOD AND LOST THEIR LIVES. YOU ARE NOW LIVING IN THE SOIL OF A FRIENDLY COUNTRY. THEREFORE REST IN PEACE. THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE JOHNNIES AND THE MEHMETS TO US WHERE THEY LIE SIDE BY SIDE HERE IN THIS COUNTRY OF OURS. YOU, THE MOTHERS, WHO SENT THEIR SONS FROM FARAWAY COUNTRIES WIPE AWAY YOUR TEARS; YOUR SONS ARE NOW LYING IN OUR BOSOM AND ARE IN PEACE. AFTER HAVING LOST THEIR LIVES ON THIS LAND THEY HAVE BECOME OUR SONS AS WELL.

When we visited Turkey, saying you were from Australia was a ticket to being greeted warmly as brothers and sisters. Atatürk’s words have entered Turkey’s national psyche. This is the force of leadership, the resonance of generous words, and the healing power of forgiveness.

One hundred years on, we haven’t really learned much. My time alone in the graveyard at Gallipoli taught me one thing: whether you’re from this country, or that country, we’re all the same underneath. The failure of leadership, and focus on glorious victory, leads to young men resting in foreign lands under green grass and lone pines.

The whispering voices of thousands of young men: “I was a son who never really got to grow up”; “I was a father who never saw my new girl”; I was the writer of symphonies, the teacher of mathematics, the herder of cattle, the writer of stories, the poet cut down. A thousand voices, completely stilled; unless you listen carefully and quietly among the neat rows to hear: ‘why?’.

More on history and travel

Incident on the Baltic

Geoff2022-11-03T08:36:29+11:0023 Oct 2022|Tags: history, travel|

Population Exchange

Geoff2021-05-18T09:48:52+10:0017 May 2021|Tags: history, travel|

Build a wall

Geoff2021-05-18T09:52:49+10:0026 Aug 2017|Tags: history, travel|

The Patient Stones

Geoff2021-04-22T17:42:06+10:0030 Sep 2016|Tags: life, travel|

The Existential Hotel

Geoff2021-04-22T20:32:14+10:0027 May 2014|Tags: musings, travel|

Leave A Comment